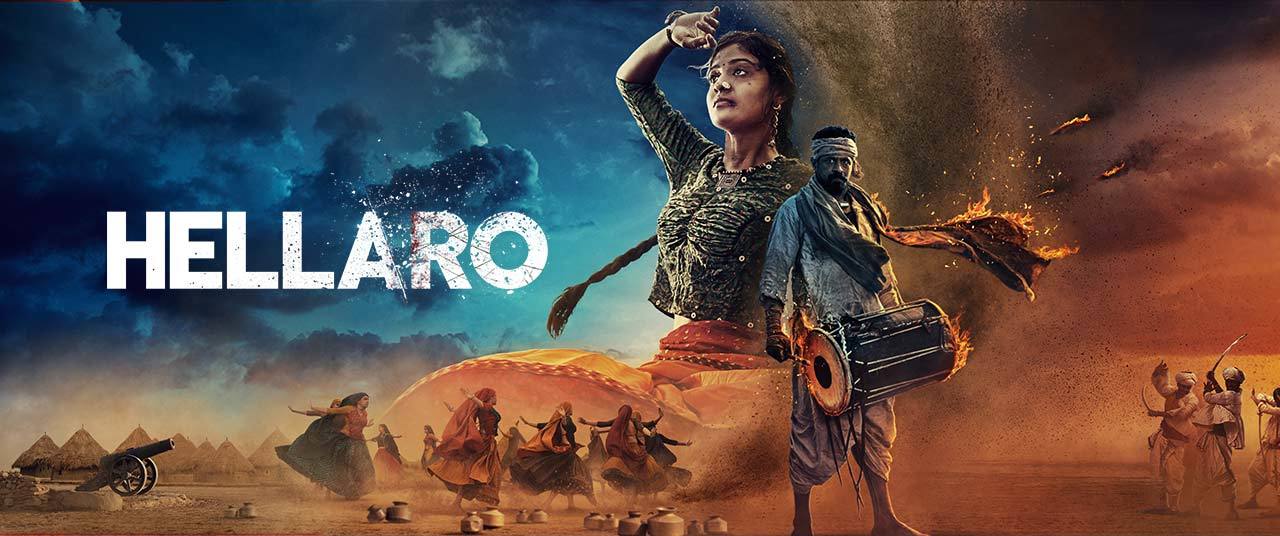

‘Hellaro’ Gujarati Movie Review

- By Nivid Desai (Gandhinagar)

India has always been home to the Sacred Feminine, a concept that is relatively controversial and debatable for the Western schools of thought. In our culture, ideology, beliefs and even at times in practice, our prime importance and veneration goes to Shakti – the Mother Goddess, the feminine divinity, the root of all life and energy. But, in the universe of a story where the moral order of the balance between masculinity and femininity is corrupted to its very core, what can possibly happen when the Shakti decides to make amends – to restore the equilibrium through the means of fearless expression and proclamation of the feminine self? This rebellion is led by a film which shines in its triumphant feminine glory through its very existence – Hellaro.

Hellaro is a practice in jarring contrasts. The film opens with the men of the community dancing to the beats of garba to ask for Maa Amba’s blessings, while the women are caged within the walls. A haunting lullaby reverberates in the background imploring them to ask the boon of a dreamless night from maavdi – their Mother Goddess. The questions this exposition intuitively raises are the ones which make us reflect upon several toxicities that we have harboured over the years, regardless of our rampant claims of acceptance, equality and progressive attitude: How deaf can patriarchy be towards the cries of its victims that it cannot notice its cruel ironies? How can they worship the Sacred Feminine and inflict torture on the women in their families at the same time? Which parts of our liberal and revolutionary heritage did we bend to match our own hunger for power? The crisp editing of the scene makes it clear that the demons of patriarchy are not only inflicted upon the current generation but it is a bitter inheritance that is passed on to the coming ones, too.

What would the joy of empathy mean to the ones whose sole experiences of companionship have been reduced to abusive domination and marital violence? In the backdrop of the seemingly infinite and painfully desolate Kutch desert, the arrival of Manjhari proves to be more than the false hopes of a fleeting mirage. Her vehement refusal to abide by the heinous restrictions of her surroundings sparks a new life in the women who had been defeated at the hands of those who derived their fickle strength by putting them down. And the women of Hellaro channelise their strength by reclaiming their most beloved part of womanhood which has been barred for them by their oppressors – garba. The film begins its victorious march from this very point!

It is laid down in the canons of literature and philosophy, be it from any corner of the world, that a well developed self is androgynous. One must naturally question then, what could this apparently jargon-like biological term have to do with the sensibilities of the downtrodden women? In that context, an androgynous self maintains a perfect balance between its masculine and feminine sides. It is a nexus of the tender and the tough. It subverts the social binaries by embracing them all at once. And In Hellaro, it is the androgyny of its dynamic characters which saves the day.

Manjhari maneuvers her self with a precise balance between her sheer innocence in enjoying her dance, and her fierce determination to lead her friends out of their misery. Mulji, the drummer, demonstrates absolute vulnerability to the miseries of his life, and at the same time, puts his heart and soul into focusing his worth of existence to the one thing he is left with in the world, his dhol. When he embraces his distraught condition and thrives on helping the women find their freedom, he is at absolute peace with himself. When the camera opens its heart to Mulji’s newfound happiness and shows a hint of a smile on his face, one cannot help but let out a tear of joy. His beloved wife and his daughter Reva, must be looking down from heaven in pure bliss.

Moreover, even Bhaglo, the jovial comic relief of the film, proves to be a silent but trusted confidant to the women. He is essentially the moral compass for the men in the film. The movie presents an emphasised undertone of his feminism throughout the narrative, ranging from his affection for the little Sita, his active support in keeping the women’s secrets and his eventual tactics to save Mulji’s life. The androgyny of the film is truly exemplified in Manjhari’s words when she claims that the world is kept alive with the help of men whom the Goddess has bestowed with a woman’s heart.

Hellaro’s feminism is also a case study of a unique kind. The underlying ideology of the film stands apart from its contemporaries in terms of its nuance and its honest portrayal. In one particular instance, the film attempts to deliver an ironic commentary on the occult traditions and superstitious practices prevalent in a regressive society. Naturally so, the women of the village are again kept at bay, regardless of the fact that the prayers are being offered to maavdi. When the little Sita asks if the men are invoking maavdi with their chants and rituals, Manjhari responds, “Maavdi aave nahi, maavdi hoy.” The Mother Goddess cannot be invoked by their futile efforts, She is always around for those whom She loves. How subtly beautiful that is! The feminine spirit always blooms where there is love and elation; it can never be curbed by those with malicious intents.

These principles, which have prepared a morale for the women in the background, are put into action in the last few minutes of the film where the women finally step up to claim their equal place. In a stark visual depiction, all the men who tried to manipulate and restrict the women from expressing the deepest recesses of their selves are shown to be standing still, while the women revel in their resplendent glory by dancing on a ferociously graceful garba. Their boundless beings radiate a divine energy, a might which can only be gifted from above. They are, in every sense, the manifestations of their beloved maavdi.

Thirteen women halt their garba in a triumphant position as the musical crescendo reaches its climax. The screen fades to black and the theatre is struck by a deafening silence. A moment passes, like a beat written at the most tense moment in a tight screenplay. A few people stand up, transfixed. A young girl from the corner starts clapping, and the domino follows. A thunderous applause erupts and the audience is electrified. I stand by my mother; a few teardrops have halted their journey down her eyes. She looks at me with gleaming eyes and says, “Joyu beta? Maavdi hoy.” (“You see this, son? The Mother Goddess is always around.”)